Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. made headlines last week when he announced that the agency would “know what has caused the autism epidemic” by September of this year.

At a Cabinet meeting at the White House, Kennedy said “hundreds of scientists” were looking into rising rates of autism diagnoses, adding that HHS would “eliminate” any exposures found to be causing autism.

Asked by ABC News at a press conference on Wednesday if that timeline was still accurate, Kennedy said he expected to have “some of the answers” by September and called it “an evolving process.”

A biennial report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published Tuesday found that, in 2022, one in 31 children was diagnosed with autism. This is an increase from one in 36 children in 2020 and one in 150 children in 2000.

On the heels of the report, Kennedy pushed back against the explanation that the increase in autism diagnoses is due to a broadening definition of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), citing instead environmental toxins as a likely cause for a significant percentage of the increases.

ABC News spoke to several public health specialists to understand if a five-month timeline is reasonable for this type of research, how that research should be done and what research has already been done to find causes of cases across the autism spectrum.

More focus, funding for autism research could be beneficial, but may take a long time

Public health specialists told ABC News that a systematic approach or national initiative to focus more research on potential causes of autism could be a good thing if that research is done appropriately.

However, they added that a five-month timeline to perform any rigorous, scientific research study is “ambitious,” and that decades of research have already been done looking at the causes of autism.

“I feel like it would be amazing if the current administration actually would put resources into a better understanding, especially as the numbers are climbing, a better understanding of potential preventative causes,” Dr. Judy Van de Water, a professor of medicine and associate director of biological sciences at University of California, Davis MIND Institute, told ABC News, but “the timeline is very ambitious, if that in fact is the timeline.”

“Regardless of what the research question is, designing the study, approving the study, funding the study, carrying out the study, analyzing the study and having it available for peer review in five months is ridiculous,” Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccinologist as well as president and co-director of the Atria Research Institute, told ABC News. “It just displays an alarming naïveté in regard to the scientific method.”

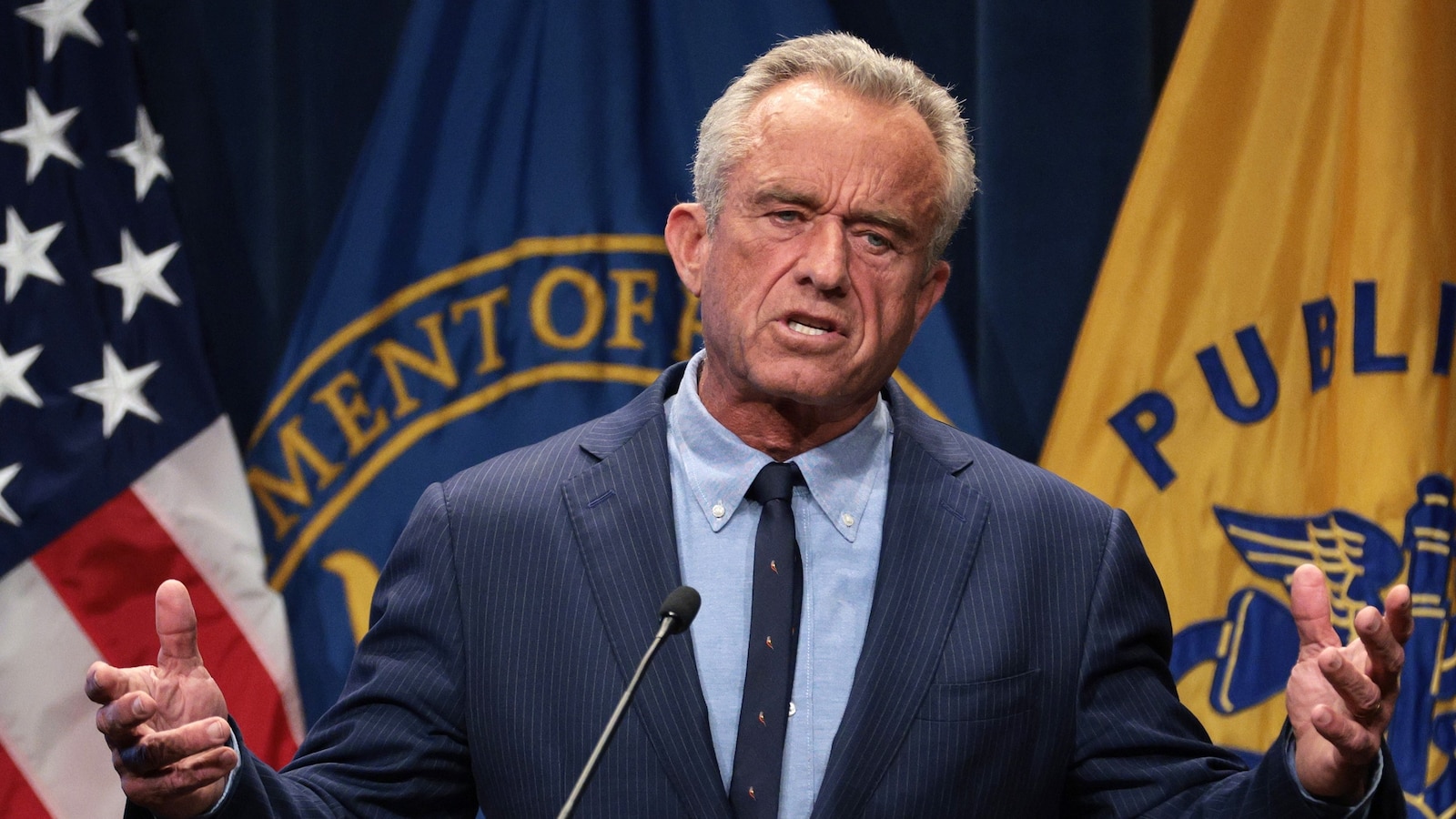

Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaks during a news conference at the Department of Health and Human Services, April 16, 2025, in Washington, D.C.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

A study of this magnitude would need to be multi-disciplinary, carefully designed, take a large amount of money to fund and would take years, not months, experts say.

“I would welcome a high-quality systems biology level study of – it’d be tough to do it across the spectrum of autism, but I’ll just use the word as a generalization – of autism. But design your study carefully. Submit the study design to widespread scientific peer review, then fund it and do it,” Poland said, adding, “that’s a very large, very expensive systems-, level, multiple collaboration with 50 or 100 co-investigators and authors. And that isn’t done in a year. It’s not done in three years.”

Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, division director in child and adolescent psychiatry at Columbia University, said it’s unclear if HHS is planning to conduct an original study gathering individuals and tracking autism diagnoses or to conduct a large-scale analysis of published research.

“We don’t know who those people are,” he told ABC News. “We don’t know the approach that they might take. We don’t know what their beliefs are. We don’t know what papers will be included, if they’re looking at existing literature, I think there’s a lot that’s unknown.”

Kennedy said the future studies would be conducted by providing funding grants to academic institutions and other researchers. Stating specifically, “We’re going to task them with certain outcomes and we’re going to have them come and bid on how to do the research,” Kennedy said.

When Kennedy was asked by ABC News’ Cheyenne Haslett if he would commit to following the science revealed by the studies, regardless of his current expectations on what’s causing the rise in diagnosis, Kennedy said yes.

Van de Water added that it’s important for HHS researchers to take a multi-disciplinary approach because ASD is a spectrum and can present differently in different children.

Additionally, like many other researchers, she pointed out that understanding what causes autism is just as important as understanding how to support those individuals.

“Understanding what the causes are, potentially preventing them, is important, but I think equally important — we’ve got one in 31 kids now — what do we do to help? That’s impactful on everyone.”

Genetics vs. environment as a cause of autism

During Wednesday’s press conference, Kennedy acknowledged research that has found a significant association between autism and genetics but claimed, without evidence, that autism is a “preventable disease” caused by an environmental exposure, which is what he wants to focus this research on.

“We know it’s an environmental exposure. It has to be. Genes do not cause epidemics. It can provide a vulnerability, but you need an environmental toxin,” Kennedy said.

One meta analysis of several twin studies found the genetic risk of autism is between 60% and 90%.

Experts have said autism diagnosis rates may be increasing for many reasons, including a combination of widening the definition of the spectrum and the types of symptoms associated with ASD, as well as people having children at older ages, better awareness and access to diagnostic testing.

Kennedy said he would be looking at “all the potential culprits,” listing mold, food additives, pesticides, air, water, medicines, and ultrasound. He also said the studies would look at associations with autism and parental factors like age and diabetes.

“This has not been done before, and we’re going to do it in a thorough and comprehensive way, and we’re going to get back to with an answer to the American people very, very quickly,” Kennedy said.

Dr. Manish Arora, founder and CEO of Linus Biotechnology and a professor of environmental medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, said both genetics and environmental factors are likely at play.

“Autism Spectrum Disorder, most of the evidence points at it being a disorder that involves both the genes and the environment,” he told ABC News. “However, the focus has primarily been on the genetics, and that has shown us that it’s not enough to just focus on the genes to decipher the complexity of autism.”

Arora went on, “We must also focus on the non-genomic part, and that’s my area of research. Yes, I believe that there will be genetic risk factors, and then environment and genetics together would determine whether a person crosses that threshold into having the spectrum disorder.”

Dr. Ty Vernon, director of the Koegel Autism Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said there has been ongoing research into the root causes of autism for decades, including research on many environmental exposures..

He said findings have shown environmental components increase the likelihood that somebody will be diagnosed with ASD, but they have not seen a study that shows any specific environmental factor don’t outright cause autism.

“There’s been studies into toxins like air pollution, pesticides, prenatal exposure to certain substances, maternal health conditions, diabetes, stress, older parents in general, birth complications, premature birth,” Vernon told. ABC News. “These are all kinds of environmental risk factors that increase likelihood that have been researched already.”

“There’s a growing understanding that there’s not one autism, but multiple autisms, and that really helps explain why there are some kind of common characteristics,” he added.

Kennedy has referred to autism as a “disease” and that the rising rate of autism diagnoses is an “epidemic.”

Experts said Kennedy’s comments make it sound like autism is an infection that can be caught and prevented, and that using the term “epidemic” may further stigmatize those who are on the spectrum or are neurodivergent.

“‘Epidemic’ definitely has a very negative connotation,” Dr. Barry Prizant, an adjunct professor in the department of communicative disorders at the University of Rhode Island and director of the private practice Childhood Communication Services, told ABC News.”It’s been applied most typically to infectious diseases and autism, as we have said, is not a disease, it is a behavioral description, and probably there are many, many factors associated with that behavioral description.”

Decades of evidence show vaccines do not cause autism

The myth that vaccines cause autism was born out of a fraudulent 1998 study, hypothesizing that the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine caused intestinal inflammation, which, in turn, led to the development of autism.

The paper has since been discredited by the scientific community, retracted from the journal in which it was published, and its primary author, Andrew Wakefield, lost his medical license after an investigation found he had acted “dishonestly and irresponsibly” in conducting his research.

More than a dozen high-quality studies have since found no evidence of a link between childhood vaccines and autism.

Still, Kennedy has shared vaccine skepticism in the past and refused to acknowledge during his Senate confirmation hearings that vaccines don’t cause autism. Researchers told ABC News that launching new studies about whether this link exists would not be beneficial.

“There just are not credible studies across decades, across multiple countries, across multiple study designs that have ever shown an association,” Poland said.

Poland pointed to several studies that have been done over the last 30 years including a 2012 report by the National Academies of Medicine that “extensively reviewed all the studies found no evidence of an association.”

According to the report, “the committee has a high degree of confidence in the epidemiologic evidence based on four studies with validity and precision to assess an association between MMR vaccine and autism.”

A view shows MMR vaccine at the City of Lubbock Health Department in Lubbock, Texas, Feb. 27, 2025.

Annie Rice/Reuters, FILE

The report identified three strong studies with negligible limitations and high precision — one study published in the New England Journal of Medicine and two published in the Lancet — that each found no association or link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

There were five total studies included in this analysis; 17 others were reviewed but excluded due to concerns with methodology or data limitations.

In 2014, RAND researchers conducted a systematic review that was published in the journal Pediatrics that found “strong evidence confirming that the MMR vaccine is not associated with autism in children.”

Poland also cited a large study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2019 that studied over 657,000 kids in Denmark born between 1999 and 2010 who were followed until 2013 and found no increased risk for autism from the MMR vaccine based on any subgrouping, even those who had siblings with autism.

“There have been large population studies that have totally debunked the sense that the so-called epidemic, which is even in question, is due to vaccines,” said Prizant, who also wrote a book titled “Uniquely Human: A Different Way of Seeing Autism.”

He went on, “One of the factors is that when a child is diagnosed with autism, it’s natural human tendency for a parent to want to know why.”

Studies also failed to find a link to autism and any childhood vaccine that contained a preservative called thimerosal. This preservative has not been used in childhood vaccines in the US since 2001.

While many questions remain about what research initiative the HHS Secretary will propose or conduct, researchers hope it will ultimately benefit people living with autism.

“I’m hopeful that we do have an initiative that is thoughtful and could benefit the autism community at the end of the day.” Van de Water said. “I don’t know that a short timeline is necessarily what you want, but in a realistic timeline that is doable, a feasible timeline.”

Jade A. Cobern, MD, MPH, is board-certified in pediatrics and general preventive medicine, and is a medical fellow of the ABC News Medical Unit.

ABC News’ Cheyenne Haslett and Sony Salzman contributed to this report.