Editor’s note: this is a guest post from Amy Brown Carver, a Martian and screenwriter, and Grid Free Minds. If you’d like to see more of Amy’s work or to reach out to collaborate, you can find her here.

I’ve been hearing rumors about Mars College for years, and it sounded straight out of science fiction: artists, AI kids, and hippies building some kind of solarpunk utopia in the desert? Turns out that’s pretty accurate, and the truth is just as interesting as fiction. Read on to learn about how Freeside found abundance rather than tragedy of the commons, and how to run your golf cart on poop gas.

Founded: 2020

Dates: January through March (roughly)

Location: Bombay Beach, California

Residents: variable, but 60-70 in 2024 and 2025

Rented or bought: Bought

Physical space: empty plot of desert one mile away from the town of Bombay Beach

Governance: Do-ocracy under two largely-hands-off founders, evolving towards a central elected governing council with a mandate to start implementing a sociocratic model (We’ll see how it goes!)

Website: https://www.mars.college/

In 2018, Freeman built the “Pod Mahal” for the Disorient Camp at Burning Man. It was two rows of 15 plywood hexapods each stacked three high on pallet rack scaffolding. It cost a lot upfront, took a month to build, and a week later when Burning Man ended, they had to take it all down. Freeman was left with a ton of plywood and pallet racks and the thought: “What if we could leave it up longer?”

Meanwhile, over 600 miles away in Imperial County, California, the derelict resort town of Bombay Beach had been attracting artists and nonconformists for decades. A friend of Freeman’s suggested he check it out, and when a plot of desert about a mile away came up for sale, Mars College was born.

This is what I’ve gathered, at least. The first I heard of it was in 2023 when my boyfriend-at-the-time told me he had been accepted “to Mars” and was leaving LA for three months.

“You’ve never even met these people.” I argued. “And you don’t know where you’ll be living. They just told you to show up and they’d figure it out. What if it’s a cult? What if you get too cold?” (He had heard of Mars through someone in his juggling community. To me, this was not reassuring.)

He told me it was a legitimate program with an AI focus and an off-grid bent. “It’s like Burning Man but with more education and fewer parties, and it lasts until March.”

This meant nearly nothing to me (except the March part), but I bought him a blanket and a water bottle and sent him off, knowing that I would never go in for something like that myself.

When I visited him a month later, I liked it so much that I enrolled officially in 2024 and 2025 and…

Fact: nobody looks hotter than when they’re holding an impact driver.

Mars is unique from many other co-living communities in that we use pallet racks and plywood to build it from scratch every year. At the end of every season, we take everything down. This effort is, essentially, crazy. And we may not do it this way forever, but for now, it affords us a few things:

-

We get to begin anew each year – a new experience, new people, with a campus layout and structures that are unique. This encourages experimentation. Have an idea? Why not try it? The worst that happens is that everyone has to put up with it for three months.

-

Having to build together encourages participation and teamwork from the get-go. If we want a classroom space, we have to build a classroom space. If we want a nice communal kitchen, we have to build a nice kitchen. Complacency is easy, but on Mars if we’re complacent, the desert is going to make us pay for it.

-

Building temporary buildings is flexible, can accommodate a lot of people, and does not fall under normal regulation.

There’s also some value in the sisyphean nature of build and un-build every year – some spiritual benefit in doing things the hard way and doing them ourselves. If we’re going to think differently, maybe it helps to live differently. And if nothing else, living in temporary plywood structures for three months – out in the wind and dust and rain – makes you appreciate permanent structures we otherwise might take for granted. (I lived in a plywood dorm room in 2025 that had a sloped roof, but the roof terminated on the inside edge of the wall rather than overhanging it. When it rained, the water ran down the interior of my wall and dripped from the ceiling onto my bed. It made me think a lot about eaves. What a good idea, eaves.)

Who would do this?

Mars College started with a creative AI focus which stemmed from Gene Kogan’s Machine Learning for Artists (ml4a) program. For the first couple of years, Gene put out the call for applications via Twitter. The first Martians were people he knew from online.

However, as the years went on, the offerings at Mars College grew. In 2024, multiple “majors” emerged, including Mars Culinary Academy, Lifestyle Engineering, Mars Theater, and Thai Bodyworks. Non-tech people started to join (or people with tech backgrounds started to specialize in non-tech things). People have taught workshops in everything from clown and acro-yoga to screenwriting and 3D printing camera lenses.

In 2025, Mars switched to a “multi-camp” model which gave these different majors more autonomy and responsibility. They could now recruit and admit Martians themselves. The camps included Mars Research (creative AI), Tool Camp (a workshop space dedicated to off-grid-living projects), Bodywork (an intensive Thai bodyworks residency), and Freeside (focused on communal living).

The number of Martians each year varies, but in 2024 and 2025, we’ve been in the 60-70 people range. (The desert is vast so Mars could grow… indefinitely.)

How people find out about Mars doesn’t exactly capture who a Martian tends to be. Martians are seasonal workers, Burners, academics, van lifers, coders, people with remote jobs, people living on savings, locals from the surrounding communities, people who travel from France, Brazil, Germany, Russia, Spain every year, and people who have nowhere else better to be.

I might be biased, but in general Martians are: passionate, physically attractive, intelligent, well-traveled, open-minded, incredibly supportive, generous even when broke, late, and often named “Sam.” They are people who, at some point in their lives, have needed to listen to themselves instead of to the wider society.

Finishing raising one another.

In 2024, I lived next to a gaggle of other Martians in an area loosely called “Freeside.” There were nine of us, and we had a central structure bedecked with solar panels that was flanked by two wings of protective bays for tents and a few very drafty cabins. Freeside was for the people who didn’t show up with their own place to sleep, who honestly showed up with very little stuff in general. We had no RVs, no converted vans, no arrangements to stay in town. We did not have our own personal ways to cook or refrigerate food and so relied on the central community kitchen.

I was deeply impressed with the other Freesiders. I had visited the previous year and so had the chance to check out Mars in person. I also came with a car and had kept my apartment three hours away in Los Angeles. Even still, I was nervous about arriving. I told myself that I would go to Mars for ten days. It was simply a ten-day camping trip, and if I didn’t like it, I could leave.

Seven of the other eight Freesiders, however, arrived sight-unseen by plane carrying only their luggage. They had no car, no other means of transportation. Two were from the East Coast of the United States, and five (coincidentally) from France. These were laid-back risk takers, hard-core adventurers. Freesiders fell into the role of scroungers, Martian riff-raff, but by the end they were the people on Mars who felt closest to family to me.

As I mentioned, 2025 saw Mars restructure into a “multi-camp” model in the style of Burning Man. Each camp was responsible for its campers’ physical well-being. Gene, Freeman, and Josh Jet were set to lead the “AI Camp” and put out a call for other camp leads. Within the announcement, Freeman mentioned somewhat casually that he thought it would be a good thing if someone were to bring Freeside back as a camp.

That got me thinking. Freeman was right. There was value in having a place for Martians who didn’t already have housing, who could arrive from overseas or out of state, who needed for one reason or another to live on the cheap. I knew that many of the other Freesiders were not planning to return, and I thought that whoever organized Freeside should probably have lived in Freeside. So I volunteered.

I recruited Ben, fellow Freesider and “Grumpy Grandma” of the communal kitchen, to help me. Grumpy Grandma is the term for the person who doesn’t want to act as anybody’s mom, doesn’t want to be nagging and/or cleaning up after everyone, but who also had standards for comfort and cleanliness. Acting as Grumpy Grandma is a public service. Listen to Grumpy Grandma.

Organizing Freeside was terrifying. Our emphasis and main offering was providing housing and kitchen space. I mostly promised to provide buildings, and I am not a builder. What’s more, in 2024 we built a massive structure over the course of months, and people were feeling burnt out. When I asked for support, the builders were non-committal. Even now, thinking back to that time, I can feel an echo of the dread in my gut, in my groin, in my toes. People would be coming – some from overseas – and they would be relying on me for water, shelter, access to groceries, transportation, power, a kitchen. I didn’t want them to be miserable. I didn’t want them to have to go home.

An army marches on its stomach.

I didn’t know how to motivate people. Should I make them t-shirts? In the end, I decided that if I couldn’t build Freeside personally, I would feed the builders instead. The nearest grocery store to Bombay Beach is a 40-minute drive away. There’s one bar/restaurant, The Ski Inn, and depending on how recently it’s lost its whole cooking staff, the food service can be slow. And in the beginning, there’s nothing on Mars, no kitchen or refrigeration. In addition to bribing the builders, my thought was that having everyone individually arrange their own food was wasting a lot of build time. It wasn’t unusual for people to break for lunch, head to the Ski, and then not come back. While it looked like I was providing a public service, my intentions were entirely self-serving. (Please, help build my thing!)

I recruited Catherine, a Martian and professional chef. She sent me the recipes and the grocery lists. We had a budget of $1,000 ($2.50/person/meal, feeding 20 people lunch and dinner for ten days). I then coordinated with Martians who had houses in town, asking them if we could use their kitchens. I asked/assigned people to be cooks, and we were off. The result was really really nice. Every day for lunch I would bring out sandwich fixings and every evening for dinner we’d eat a meal together and hang out. We started with a feeling of warmth and community, and it was the beginning of a theme for me for the year – the more we did things (like meals) as a group the cheaper, nicer, and more effective they were.

The other thing that was a boon to getting Freeside built was meeting AJ. If this were a fantasy story, AJ would be the wizard the protagonist meets in Act II or the special amulet that allows the hero to accomplish the impossible feat in front of him. AJ is a little weird in the sense that he only likes to build. AJ lives about two hours away from Mars in what’s essentially a curated junk yard, and AJ’s contribution was a revelation: he brought windows to Mars. At Mars BAJ (Before AJ), we built with plywood, pallet racks, doors, fabric… and that was it. So AJ’s addition of glass windows really added some glamour to the place.

The creative and technical work done at Mars.

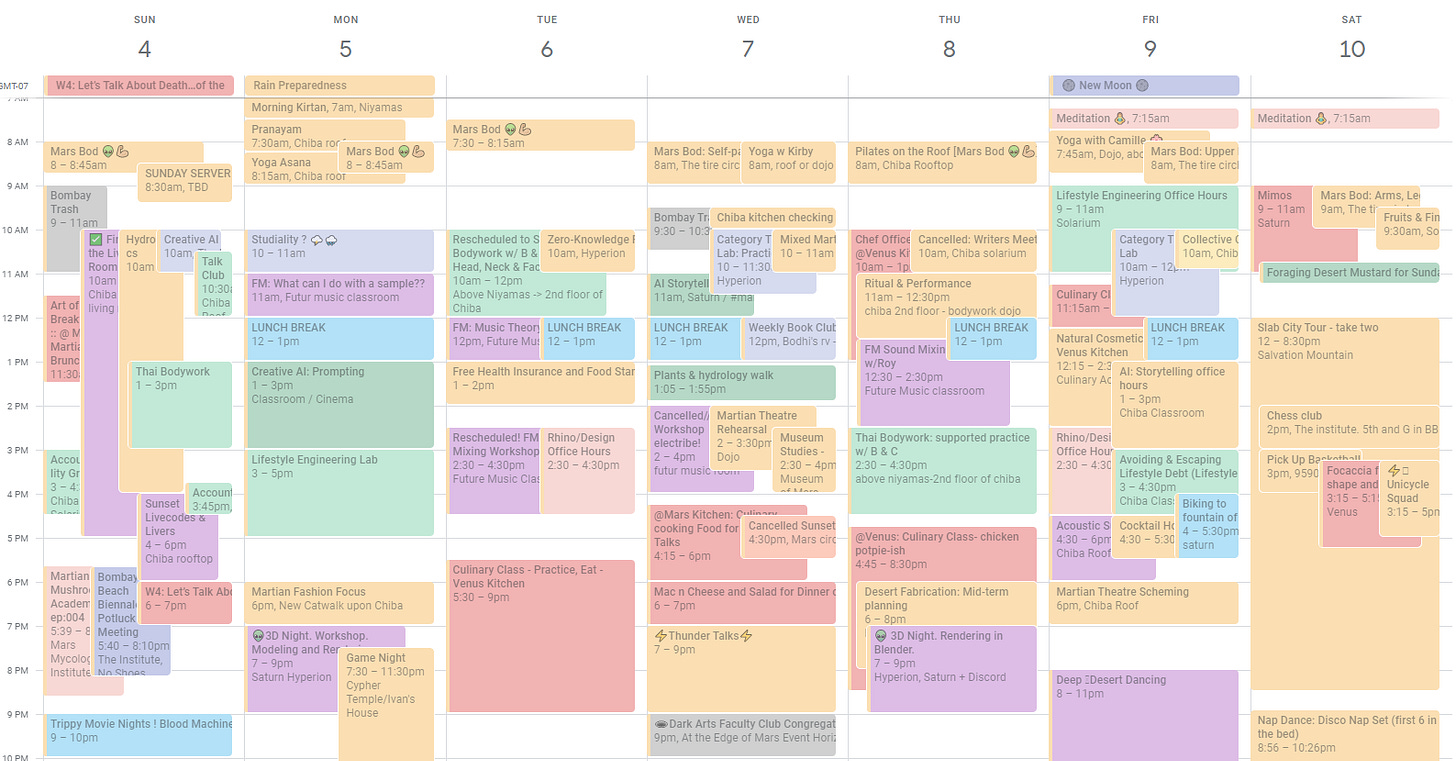

In addition to living together, there’s the “college” portion of Mars College. Zooming back out from Freeside, Mars as a whole is structured around an unconference-style format – meaning anyone can host a class. All they have to do is add it to the shared Google calendar.

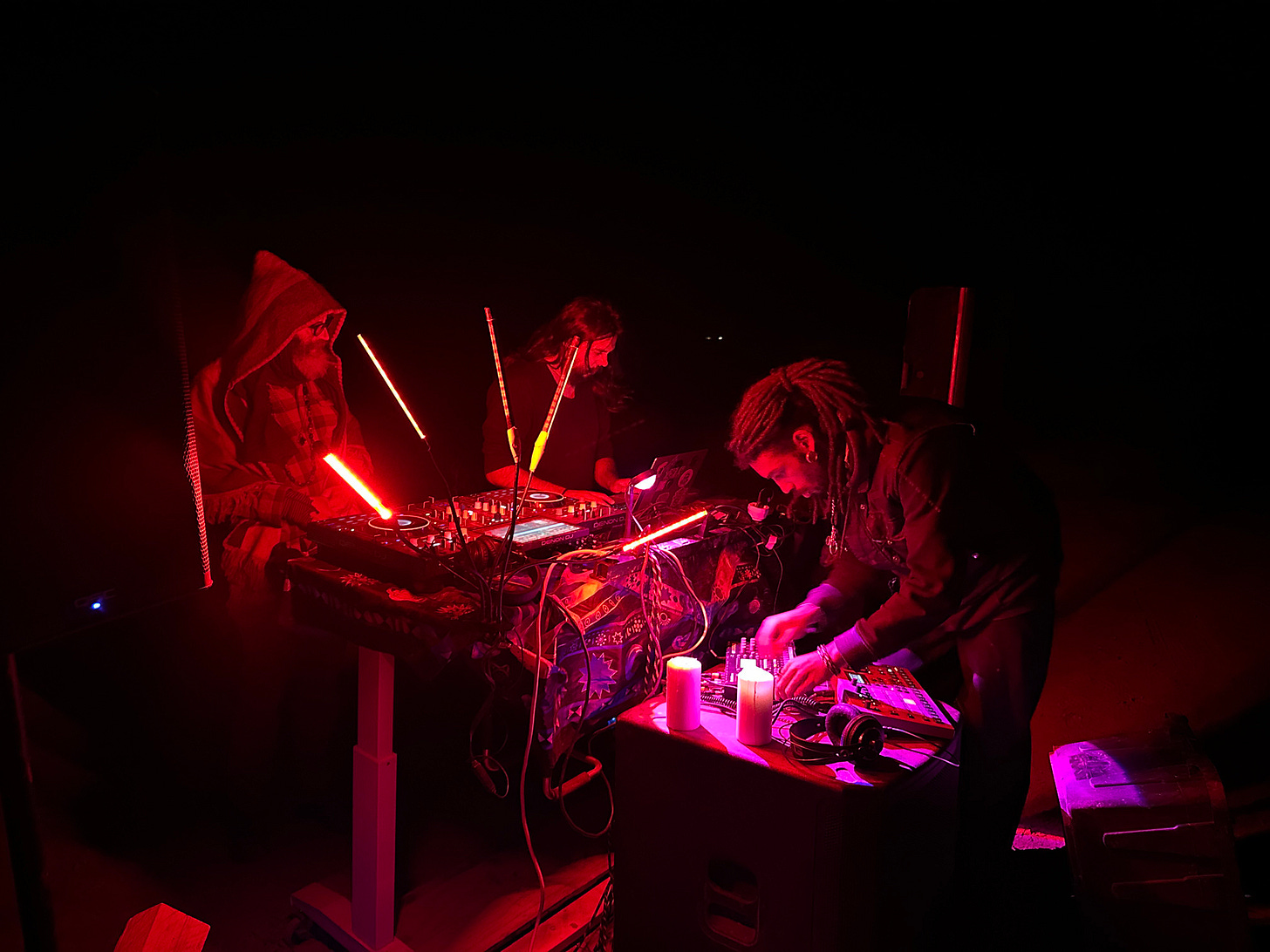

Thunder Talks are on-going Mars traditions. They give Martians the chance to stand up in front of everyone and present who they are and what interests them. It gives Martians a quick way to get to know one another and to find potential collaborators. Anyone can sign up to give a 15-minute presentation on whatever they want.

Martians also work on their personal projects throughout Mars. To highlight a couple:

Solar Sam, who runs our solar system, expanded into “poop gas” this year, a process by which he takes poop and transforms it into usable fuel (by using solar energy to safely and hygienically sequester its carbon).

Charlie designed, made, and demoed the early stages of a 3-D mud printer. His larger idea is to print houses and other structures out of material that is more sustainable than cement.

Cat painted portraits and ran an immersive experience asking participants “Who are you today?”

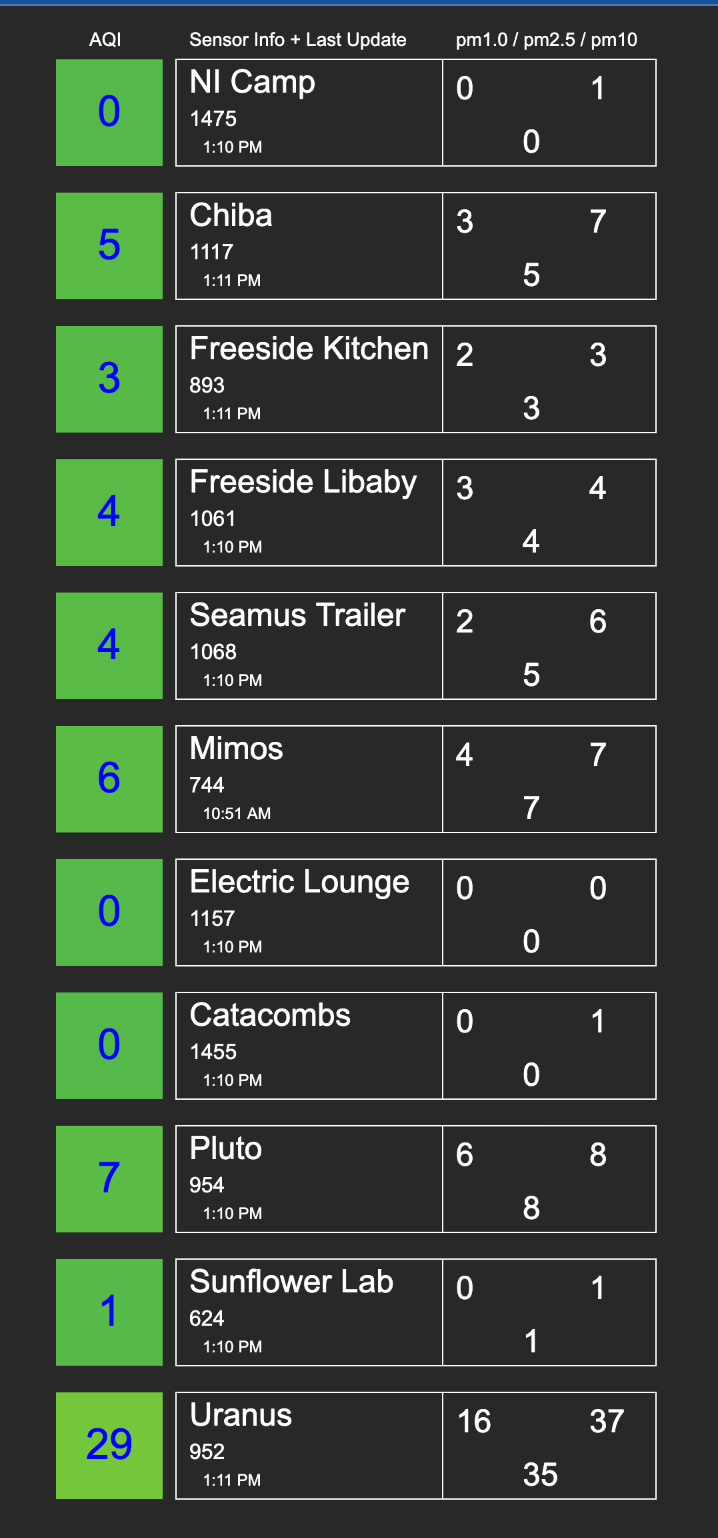

Seamus ran an air quality monitoring network that gave real-time updates on the air quality of multiple Mars locations, to track particulate counts during intense dust storms. As a side benefit, you could tell in real time when someone was cooking in one of the kitchens or smoking at Mimos, the Martian-run coffee spot and hangout.

Vincent used Eden to create an AI parody trailer for “The Six-Million Dollar Duck” and an AI parody commercial for Mars (which contains too many people’s likenesses to make public), but which includes the lines:

Do not take Mars College if you have a history of rational decision making

Allergic reactions to communal chores

Or have long-term career goals.

Mars College is not a cult.

Cults usually have a charismatic leader and a clearly defined ideology.

It’s more of a BYOB cult potluck,

Where your weird new friends ask you to participate in rituals that they just made up.

Chebel wrote and directed “Infinite Land,” a science-fiction short film.

And Jordan single-handedly rebuilt “the dome,” a much-loved short-lived cozy space during Mars 2024. It was covered with semi-transparent plastic used for projection screens and filled with blankets and mattresses before a windstorm mangled it past all recognition. In 2025, before rebuilding, Jordan gave a presentation that stuck with me. He showed a video of the twisted collapsing dome and talked with enthusiasm about embracing “catastrophic failure.”

If this ain’t a vibe…

Ben and I, when we were recruiting and admitting people to Freeside, were looking for people who had independent projects and who liked living together. We put an emphasis on coziness, and while not mandating a meal plan, we looked for people who liked cooking, who generally liked hanging out.

When the two weeks of official build came to a close, the building of Mars wasn’t actually finished. So we took an additional week (two weeks? Three weeks? Does build ever really end?) as a camp to build. I shifted from all-Mars build crew meals to meals for Freesiders, plus (crucially) anyone else who was currently helping to build Freeside.

It paid off. Freeside was the first habitable space on Mars. We threw the first party. Our accomplishment felt stunning – we were a cozy place to be in the middle of the desert.

A quote by Kurt Vonnegut came often to my mind: “I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, ‘If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.’” I expressed this to Jack (at 21 years old, the youngest Martian) who misremembered it as: “If this ain’t a vibe, I don’t know what is.” And that stuck.

Freeside was right next to a giant warehouse belonging to Tool Camp, which – you might guess – was made up of people who build things. By the end of that third build week, almost everyone in Tool Camp was helping Freeside build and, in turn, sharing dinners with us. They had planned on building out their own kitchen and starting their own meal plan. But we were working so well together, that they asked if they could just join us. Our total number came to 14 people.

Pleasantness is important work.

Most Freesiders did not have a car, and one of the things Ben and I had agreed to was to make sure everyone had access to groceries. I was making weekly grocery runs to Indio, the town 40-minutes away, and the lengthy list was leaving me stressed and worn out. Carlota and I sat down to think of a better way, and the Freeside Meal Plan was born.

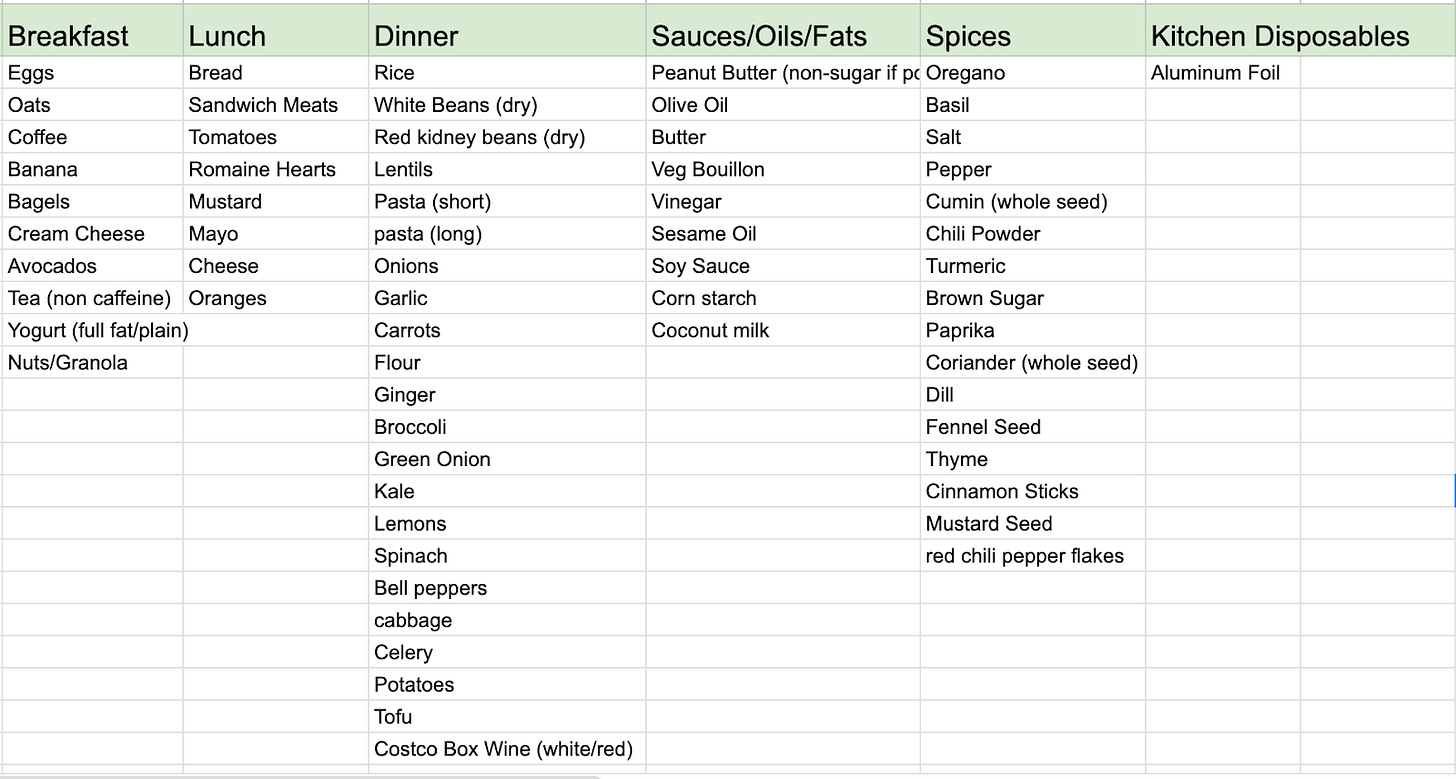

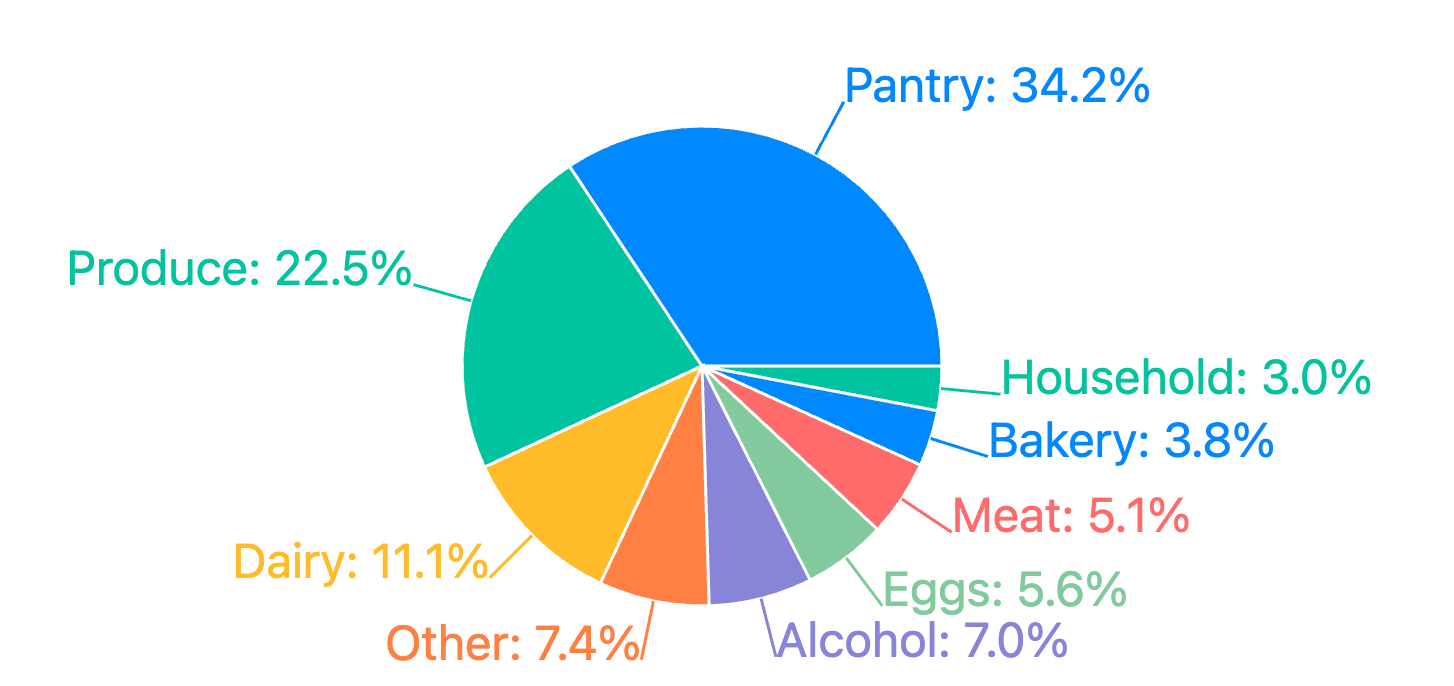

I made a list of items that I would agree to stock every week and then went around to the main cooks in the group for their edits. Once all the cooks were happy, I told everyone that they would be allowed three personal items a week. As it turned out, the communal list was extensive enough that personal requests disappeared altogether. We used the Spliit app to track expenses.

Everyone was free to use as much of the communal groceries as they wanted at any time, and for breakfast and lunch people were on their own. For dinner, people would sign up on a whiteboard volunteering to cook. Cooking shifts were not required and some Freesiders didn’t cook all season. Even still, except for two nights, someone made dinner – and frequently an amazing dinner – every night for all three months of Mars.

Buying and sharing groceries as a group had many benefits:

-

I was the only person, out of 14 people, who went grocery shopping each week. That saved a lot of gas and a lot of people’s time. Plus, since I went every week, I got good at it and started to like it.

-

Because we were largely sharing all of our food, we didn’t have the classic roommate conflict of Who ate my x? All of the food belonged to everyone. If we ran out of something early, the following week I just doubled the order.

-

Since the food belonged to everyone, that meant the random molding mystery items at the back of the fridge also belonged to everyone. If anyone saw something gross, that person had full license to throw it away.

-

Buying in bulk saved us money. A surprising amount of money. The average food cost per day per person came to $5. It actually started messing with my head – Why is society, by way of the grocery store, incentivizing people to live in households with 13 other adults?

Of course, a big part of why the Freeside food costs were so low is that the labor costs of shopping, cooking, and cleaning were not included. So it wasn’t enough to just pay your $5, everyone who was part of Freeside needed to do chores.

And there were plenty of chores to do. We needed to haul fresh water in and gray water out. We needed to wash and dry the dishes, remove trash, wipe counters, sweep floors, and do laundry.

One of the ways we relieved this burden was by doing a weekly Mars Care. Created by Ben, Mars Care was every Friday morning at 9:30am. Everybody using the Freeside kitchen got together for emotional check-ins, and then we deep-cleaned the kitchen and reset the space. It felt easier to do the jobs you didn’t want to do when everyone was there doing them too. It also ensured that cleanliness stayed in check – no matter how bad things got, at least everything would get cleaned once a week.

It also helped build a culture of teamwork and group effort. Ben and I would have burnt out if we had to organize and run Freeside all on our own. Instead, Freeside was an experience we all created together. In preparation to write this essay, I read the Supernuclear case study on Ski Cult, and this resonated with me:

“The biggest lesson was the challenge and necessity of shifting people from a consumptive mindset to a participatory one. I initially took on a lot of the burden of organizing (bringing people together, presiding over discussions about rules and norms, making decisions when consensus was impossible or infeasible) but quickly found myself burning out. It was only when one of the members stepped up and sent out a pair of questionnaires, without any prompting or input from me, that I realized that I had been needing other people to be more involved and collaborative the whole time.”

We had two whiteboards in the kitchen where we attempted to make chores legible and accounted for. This felt subtly radical to me because it highlighted work that, in larger society, is often done by women (or, if a household has the money, to someone those women hire). It’s shuffled along, belittled or left invisible. In Freeside, we attempted to make domestic work just as important – and just as shared – as the other creative or technical work done at Mars.

There is too much to say about Mars for just one person writing one essay. I focus on Freeside here because it was the camp that I helped create. I just touched on Tool Camp, the Mars makerspace for experimental low-cost, off-grid, and open source infrastructure. I don’t say anything about Bodywork, the camp of eleven people across the desert from us, who could (should?) have an essay all to themselves. They also lived together, but did so in many ways that differed from us. For one thing, they were all following a shared curriculum, training together for hours every day. They also divided chores and handled finances differently and practiced circling techniques to foster group communication and closeness.

Throughout the 2025 season, we had multiple cross-camp meetings. These were sessions open to everyone in which we discussed how Mars was going and what we’d like to change, either immediately or in the future. A common refrain was a call for a more established form of governance. By the end of the 2025 season, we settled on an elected five-person council (plus the founders, Gene and Freeman) given large leeway and trust to organize next year’s Mars with the mandate to also move towards a sociocracy-based system.

As with everything else about Mars, the Council will be something of an experiment. We start from blank desert every year and build something new. Every year is strikingly different. And I expect Mars 2026 will be no exception.

Mars has an application process (hosted on its website) that opens around October of each year. If anything in this essay has piqued your interest, we’d love for you to apply. Follow the Mars College substack to stay informed for upcoming events.

This is part of an ongoing series of deep dives on coliving spaces. To see others, visit the Supernuclear directory. If you want to contribute a case study of your community, awesome! Please find guidelines for submission in this post.

Suggested further reading:

How to start a school with your friends

Case Study: Feÿtopia

I wrote this after spending a week at the Chateau du Feÿ & interviewing a few of the founding members of Feÿtopia.